Optimizing for Workloads: Linux Spinlocks vs Mutexes

Introduction

Operating systems form the backbone of modern processing environments. Millions of lines of code are responsible for enabling programs to easily execute on a given machine. These programs must share the machine’s resources, such as processor cores, volatile memory, peripheral devices, and persistent media. Virtualization and resource management is accomplished by the underlying operating system, which ensures the system operates correctly and in an efficient manner. Machine resources should be largely devoted to the user applications which mandates careful system design and implementation.

User applications must interact with the operating system to effectively use the machine’s resources. This interaction is realized using a set of well-defined interfaces (APIs) which programs can call to instruct the operating system to perform required actions. Modern systems export hundreds of system calls to the user application which each have very specific actions they perform. There are five categories of system calls: process control, file manipulation, device manipulation, information maintenance and communication. By combining and mixing the usage of these various system calls, user applications can accomplish a wide variety of tasks on a given machine, but cannot take over control of the hardware or steal data from other programs.

Process control refers to the operating systems ability to run programs at various times while maintaining each program’s illusion that full machine capabilities are available. The operating system will tend to swap out tasks to provide fair usage of the physical processing resources. Modern hardware systems often have multiple physical processing cores which can be used to run different programs in parallel, or can be exploited by a single program for increased processing throughput. When a single program creates multiple threads of execution, careful thought must be placed on how these threads interact and share common data to ensure program correctness while simultaneously realizing the potential performance gains. The operating system provides various synchronization primitives which the application can use to maintain data consistency and algorithmic correctness.

Problems

Maximum processing throughput naturally demands concurrency and full utilization of the available processing resources. Critical sections of code, where only a single thread can execute at a time, are common in high performance concurrent applications. Modern operating systems provide simple locking primitives to enforce the single thread constraint. Two common lock types are the spin lock and mutex. Each lock type creates a barrier to critical sections, thus maintaining program correctness. However, spin locks and mutexes are internally implemented very differently, leading to significant performance differences in various common workloads. The following sections explore this further.

Approach

Multiple workloads are designed to exhibit the differing performance observed between spinlocks and mutexes. These workloads are benchmarked on a typical user system and performance metrics are collected for analysis. Care is given to ensure the resulting data and conclusions are repeatable. When possible, workloads are designed to represent a wide range of use cases so more widely encompassing conclusions can be made. The rest of this article describes the various experiments performed as well as the results. Conclusions are made which highlight the major observations which can be utilized when developing user applications.

Experiments

All experiments are performed on a consumer desktop PC running Linux 4.4.8. The PC has a quad-core Intel i7-2600K processor with hyper-threading to enable eight hardware threads of execution. System memory available is 24GB. The persistent media is a 1TB hard disk drive (HDD) from Western Digital with 7200 RPM rotational speed and 32MB cache. The filesystem is ext4.

Concurrency

While many different primitives exist to help applications manage concurrency, locks remain an easy-to-use solution. When one thread “holds” a lock, other threads are prevented from also holding the lock. Spinlocks are implemented such that the thread that fails to acquire the lock continually retries to get it. This wastes CPU time, but can result in better performance. Mutexes behave similarly to spinlocks at first, but after a few failed acquisitions, the thread is put to sleep until the lock is available. This allows the CPU to be used by other threads.

Workload

The performance of the locking mechanisms depends on multiple factors. In this analysis, attention is given to the time spent in the critical section of code, as well as the number of threads attempting to acquire the lock. A simple workload is constructed which creates an array of threads to do work. This work consists of 100 accesses of the critical section.

pthread_t threads[NUM]

lock_t lock

critical()

{

lock(&lock)

for 1 to WORK: NOP

unlock(&lock)

}

void *work(void *arg)

{

count = 1

while count <= 100:

critical()

count++

}

main()

{

init_lock(&lock)

// PROFILE START

for i 1 to NUM:

pthread_create(

&threads[i],

NULL, work)

for i 1 to NUM:

pthread_join(

threads[i],

NULL)

// PROFILE END

}

Listing 1: Workload implementation for spinlock vs. mutex comparison.

At run time, a parameter is passed to the program to set the duration a thread spends in the critical section. By sweeping both the number of threads and the duration of time spent in the critical section, interesting results emerge. See Listing 1 for implementation details.

Results

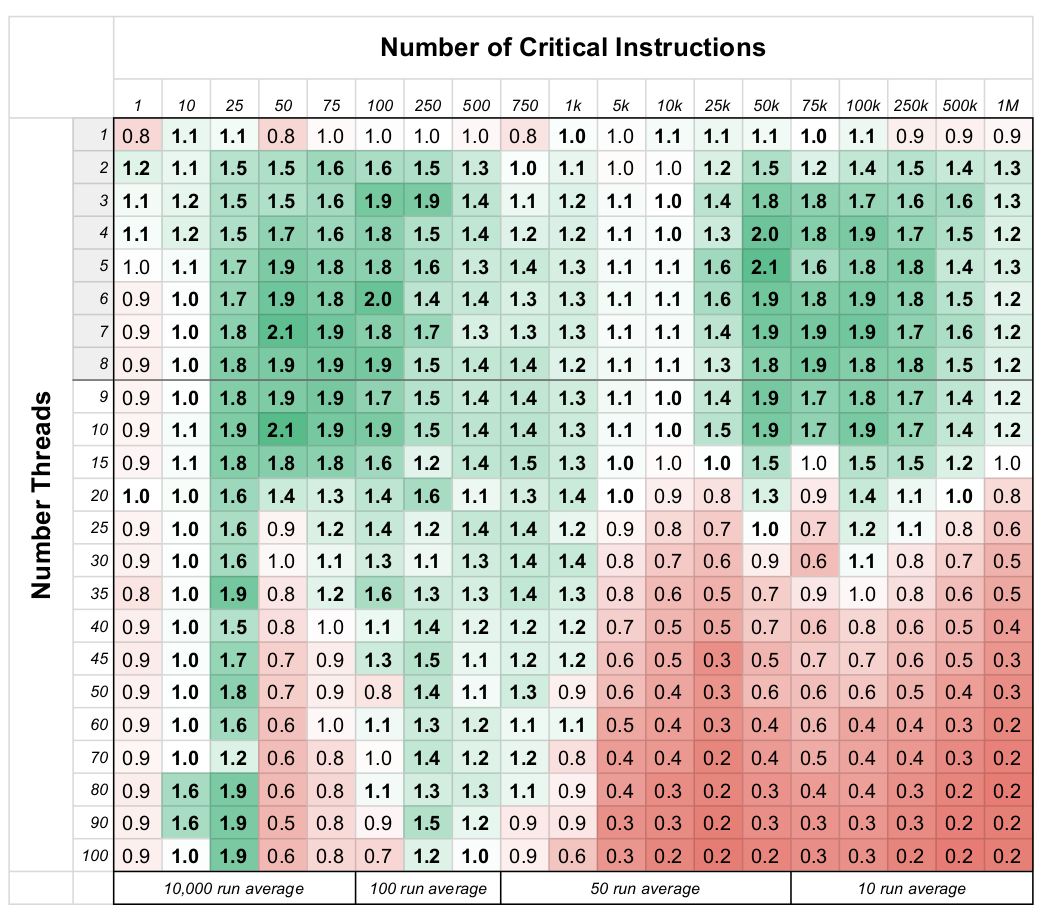

Figure 3 shows a plot of relative performance of the spinlock to the mutex. Each cell in the plot contains a value which is the ratio of performance. A value of 1.0 indicates both the spinlock and mutex have identical performance, while a value of 2.0 indicates the spinlock version of the workload completed its task twice as fast as the mutex version (normalized by total number of threads). A wide range of time spent in the critical section was evaluated, with number of critical cycles varying widely in magnitude (1 to 1M). For each of these values, a range of thread counts were evaluated, ranging from one to 100 threads.

The wide range of thread count and critical instruction count leads to interesting data which can help inform the decision of when to use spinlocks versus mutexes. General notions are that spinlocks are inefficient and waste CPU time, while mutexes allow efficient allocation of processing time. Figure 3 clearly shows that there is much more nuance relating to which lock type performs better.

Coloring is given to the plot to show areas of general performance:

- Green indicates values greater than one (spinlocks perform better)

- Red indicates values less than one (mutexes perform better)

Evaluation

For program thread counts less than or equal to the number of threads available on the given machine, spin locks always perform as well or better than mutexes, in some cases up to twice as well.

This can be explained because mutexes must put a thread to sleep and then later reawaken it, which is a very expensive process. As long as there are not starved threads which require the CPU, having a thread spin on a lock and simply wait for it to become free leads to significantly higher performance.

Naturally, as the number of threads is increased to more than the physical hardware supports, the threads must share the CPU. Programs that have critical sections with more than 1k instructions and more than the hardware allowed number of threads show that mutexes allow much higher performance. This is because the blocked thread is put to sleep, which enables another thread to do work.

Finally, it can be seen that for workloads with more than eight threads but less than 1k critical section instructions, spinlocks perform very well. This could suggest that the operating system must run approximately 1k instructions to put a thread to sleep and wake it up. Therefore, just keeping the thread awake and spinning is better for performance.

Conclusion

Careful study of various workloads for thread synchronization is performed. Both spinlocks and mutexes are tested in a wide range of combinations of thread count and critical section instructions. It is shown that for workloads with less than or equal number of threads than the physical hardware allows, using spinlocks can lead to higher performance (up to 2x). However, when critical section instruction count increases to above five thousand instructions and thread count rises above hardware supported amount, mutexes will perform better, as threads are put to sleep to make way for other threads to effectively use the CPU. Users must take into consideration the number of cycles in an application’s critical section to determine appropriate lock type.

This analysis was performed during Spring 2019 for University of Wisconsin-Madison course COMP SCI 736: Advanced Operating Systems.

New Post Notifications

If you read this far into this article, you might be interested in subscribing for email notifications about future new posts I write. I will never spam you! Every few months, I write a new article for this website, and will send you email about it. You can unsubscribe at any time. Thank you.